The ability to plan investigations is the third skill area covered in this series of primary ‘scientific enquiry’ blogs.

What are the thinking skills involved in planning?

Planning an investigation is a demanding skill. It relies on a learner’s ability to think ahead (as does the skill of predicting) and to visualise the steps that are needed to solve a problem. This is clearly higher order thinking. Where the problem involves different factors, the ability to manipulate and control variables is an essential skill. This is again characteristic of abstract thinking at higher levels.

So the question arises – ‘How much responsibility should learners take in planning enquiries, especially in their early years in primary school?’ In Science education, great emphasis is put on the skill of planning. Planning enquiries gives learners the opportunity to find things out for themselves and behave like young scientists. When planning their investigations, learners experience the excitement of taking charge of their own work, and making decisions for themselves motivates them to see the task through to its conclusion.

Having said that, support and guidance is crucial to the success of planning enquiries in the early years. To set young learners loose on a scientific investigation expecting them to plan and carry out the testing themselves at such an early stage in their education is a recipe for chaos in the classroom. It will result in plenty of exploration, but without the clarity of purpose a good plan will bring, and can result in confusion, frustration and poor behaviour.

Therefore, the teacher’s role in the first few years of primary school in setting the foundations of planning skills are critical to young learners’ perception of science. The skillful teacher will introduce these challenging thinking skills through careful questioning, guidance and modelling before practical investigations. Some tips to help you in this difficult, but rewarding, task are described in the strategies discussed later. In the early years, these will help learners who are used to thinking at a concrete level, to start making the transition to abstract thinking.

What does progression look like in the skill of predicting?

As part of their developing powers of planning, learners will move from:

- needing support to plan a simple test and requiring significant teacher input. (Some may not yet respond appropriately to prompts offered by the teacher) to suggesting what to do in a simple test, responding to a more open-ended question from their teacher

- to planning a simple ‘Which type …?’ test, suggesting some factors that need to controlled, using a planning frame in a teacher-led discussion to responding to the teacher’s suggestions in a range of fair tests, and starting to put forward their own ideas when completing a class planning frame

- to using a planning frame, as part of a group, to ‘vary one factor while keeping the others the same’ with the aid of a planning frame, as well as selecting some of the equipment needed in an investigation.

- deciding on the appropriate approach needed to gather the necessary information or data to answer the scientific question under investigation

- to deciding on the key factors themselves and controlling other factors in more complex investigations, writing up their plan after completing a planning frame.

So how can we develop planning skills?

Here are some strategies that we can use to develop planning skills in scientific enquiries:

STRATEGY 1 – The challenge of an ‘unfair’ test

To set our youngest learners off on the long road that eventually leads to a full understanding of how to plan an investigation, we can start to stimulate an appreciation of the need for fair testing in simple investigations. Simple investigations can be defined as those set in everyday contexts, with a relatively small number of variables to think about.

In these early investigations, the teacher’s introduction to the task can include a ‘faulty’ demonstration of how we might carry out the test. This will be a model of poor practice! The teacher will deliberately, and quite obviously at first, show the class a test in which more than one variable is changed at the same time i.e. set up a blatantly ‘unfair’ test.

For example, the teacher might vary the number of layers – as well as the type of material – when testing which is best to repair the roof on a doll’s house. She then goes on to change the amount of water dropped on to the different types of material as well. This can develop into a game in which the learners enjoy ‘spotting the mistakes’ (a good pantomime routine can be started – “This is a fair test”, “Oh no it isn’t!”, “Oh yes it is!” etc. etc., culminating in the teacher asking “Why?”).

As learners become more skilled at recognising a fair test, the errors can become more subtle and can be used as a means of targeting questions to challenge learners of differing attainment.

Learners themselves can be used to model a test – ‘scripted’ by the teacher if necessary – that is ‘unfair’. As learners gain more experience, some children will be capable of putting their own ideas into such a role play. Another technique is to let the learners who are demonstrating the method go through a test, with a running commentary by the teacher, with no interruptions from the rest of the class. The class can then be split into groups to see who can remember most mistakes at the end.

STRATEGY 2 – Know your variables – and start simple!

In the early years of primary science, any fair tests you introduce are likely to be concentrating on investigating the effects of categoric variables. A categoric variable can be thought of as one that is described by a word.

Examples include the ‘type of material’ (in the investigation ‘Which material is most waterproof?’) or the ‘colour of the jelly’ (in ‘Which type of jelly dissolves best?). These are ‘Which-type’ consumer tests that pit one type of product against its rivals. (Note that this type of Which-test can be used to develop the skills needed to draw bar charts – See the ‘Recording and Presenting’ skill blog later in this series).

This type of variable – the categoric variable – is easier to deal with than the continuous variables (i.e. variables can have a range of numerical values) that learners will eventually have to deal with later. Categoric variables are usually ‘real objects’, such as different toy cars to test on slopes, and so learners can actually see the different values of the variable they are going to change (called the independent variable). Therefore, varying this type of ‘concrete’ variable is more accessible to young investigators.

Younger learners can visualise the competition between the different values of the categoric variable (the analogy of a race can be used, ‘Would it be fair to let someone start 10 metres in front of everyone else?). And the simplest of these investigations is when the fair test involves just two values of the categoric variable, i.e. ‘one against another’. In this simplest of scenarios, the youngest learners start to grasp the meaning of a fair test.

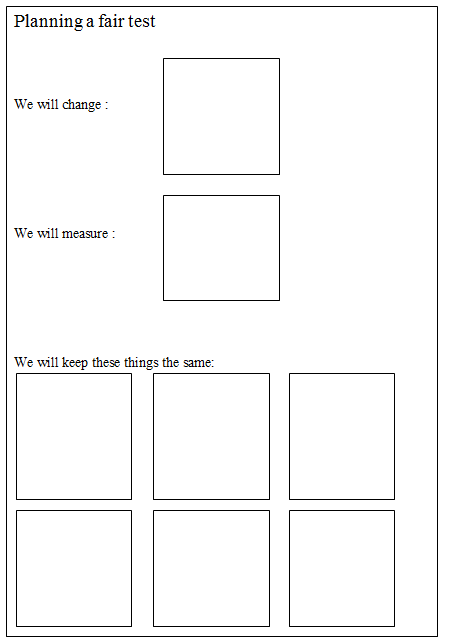

STRATEGY 3 – Introduce a planning frame for fair tests

At the end of Stage 2 and beginning Stage 3, we can introduce a class planning frame to help learners make sense of the ‘fair testing’ type of enquiry.

(See AKSIS project ‘Developing understanding in scientific enquiry: ASE publications’). The teacher should act as a guide, modelling the use of the planner shown below (developed from an original idea by Anne Goldsworthy):

The teacher introduces an investigation with the planning frame poster on a wall, board or stand behind her. She has a supply of sticky ‘post-its’ to record learners’ suggestions before attaching them to the appropriate squares on the planning frame.

Here is one way to use the planning frame for investigating toy cars on ramps. The teacher starts off with an open-ended question to the class:

TEACHER: “What might affect the way a toy car will roll down this ramp?”

A child offers an idea, which the teacher records on a ‘post-it’.

She sticks this in one of the boxes at the bottom of the planner.

She hasn’t mentioned fair testing as yet!

TEACHER: “Good! Any other ideas?”

As children suggest more variables (i.e. “more things that affect the rolling of toy cars”), they too are recorded and stuck on the poster under ‘We will keep these things the same:’

TEACHER: “And how might we measure how well the car rolls down the ramp?”

The teacher fields suggestions, recording and sticking the one that says ‘The distance the car rolls’ and in the box opposite ‘We will measure:’

At this point the teacher removes one of the variables from the bottom of the planner.

She chooses the post-it with ‘height of the ramp’ written on it.

TEACHER: “We are going to see if this affects how far the car rolls.”

She slowly moves this ‘height of the ramp’ post-it up to the box labelled ‘We will change’.

TEACHER: “So we will change the height of the slope and measure the distance the car rolls each time. All the other things that we said might affect the way the cars roll, we must keep the same – just in case they do affect how far the car rolls.”

(Teacher is pointing to the post-its stuck under ‘We will keep these things the same’ at the bottom of the poster)

The teacher then moves another post-it from the bottom of the poster (i.e one of the things we keep the same) and sticks it next to ‘Height of the ramp’.

TEACHER: “What would happen if we changed these TWO things at once? (i.e. both the height of the ramp and the other control variable placed next to it) Would we know which thing was affecting how far the car rolls?”

The teacher returns the offending post-it back to its original position with the ‘Things we keep the same’!

STRATEGY 4 – Learners start using an investigation planner themselves

Once learners are familiar with the Planning poster, they should be given the opportunity to use an A3 paper version of the poster themselves. After all, the purpose of any planning frame is to give our learners the skills needed to become independent investigators, capable of making many decisions themselves.

Working in groups, each table is provided with the A3 planner and 8 mini-‘post-its’. The group sort out the format of the planner, given a question to investigate. The teacher can then check the planner before practical work begins.

This is a popular planning tool with learners because there is little writing to do and mistakes are easily rectified by providing another ‘post-it’. This is in contrast to planning exercises which involve writing out a method which is often changed as the investigation gets under way, causing frustration.

You might consider using a computer to generate the generic planning frame, into which the learners can drag-and-drop their suggested variables typed into boxes.

STRATEGY 5 – Use a Help Sheet

Older primary learners can be supported in their planning by a generic planning Help Sheet. This reminds learners of the decisions they need to make when planning a ‘fair test’ investigation.

The complexity of the Help Sheet can be varied to meet the needs of different learners. At first, Help Sheets can be written that are specific to a particular investigation. This will reduce the level of demand compared with a generic Help Sheet.

An example of a comprehensive generic Help Sheet is shown below:

Investigation planner

You can use these questions to help you plan your investigation.

Have you thought about:

- What are you trying to find out?

- a) What do you think (predict) will happen?

- b) Why do you think this will happen?

- What are you going to change each time?

- What are you going to judge or measure each time?

- What will you keep the same each time to make it a fair test?

- How will you carry out your tests? Will a diagram help?

- Is your plan safe? Could anything go wrong and could somebody get hurt?

(Check with your teacher).

- What equipment will you need?

- How many readings will you need to take? Do you need to repeat tests?

- What is the best way to show your results? A table?…. and a bar chart? …. or a line graph?

STRATEGY 6 – Provide opportunities for learners to select equipment

Often when a practical lesson is taught, we have our equipment out and ready for learners to use when they enter the room (often after lunchtime!) – a good example of effective lesson planning and classroom organisation. However, we want our learners to be involved in decision making as much as possible, and ‘selecting equipment’ is one way that they develop ownership of their plan.

To combat this problem, some teachers get their class to plan an investigation at the end of the previous day. Part of this half-hour session is the production of a list of equipment needed to conduct the investigation next day. The teacher collects in the lists and can assess the progress of each group. Whether you can provide the chosen equipment that the learners select, of course, is another matter!

Another opportunity to assess this skill arises when an investigation involves measurement, so you can provide measuring equipment with a range of scales available for learners to choose from.

STRATEGY 7 – Giving learners opportunities to make decisions

This presents us with a problem as organisers of science lessons, bearing in mind the resources available to us, the constraints of the school day, and the demands of the Cambridge Schemes of Work. However, we can still allow learners to raise their own questions to investigate within the context of any Scheme of Work that may well define a particular investigation, and hence your school will be resourced to deliver that specific activity.

Starting off an investigation using open ended questioning is the key to involving learners in deciding which question will be investigated.

If planning an investigation, such as which paper towel absorbs most water, you can start with a question that requires the learners to decide which property of paper towels to investigate. By asking, ”Which paper towel is best?”, after a few puzzled looks, learners want to know what you mean by best. When the question is turned back to them, they are free to come up with their own suggestions. For example, which is best in terms of strength, absorbency, strength when wet, cost, attractiveness, softness, etc..

So a list is generated of variables that can each be turned into a question to form the starting point of an enquiry. This also provides us with an opportunity to teach about some different ways to carry out enquiries, even if you are destined to see which paper towel is most absorbent in the lesson you are resourced to deliver!

For example,

- “How would we find out which one was most attractive?” (e.g. conduct a survey, in which ‘sample size’ is important),

- “How would we find out which one was strongest?” (e.g. elements of fair testing),

- “How could we find out which feels softest?” (e.g. exploration, using the sense of touch, again with considerations of sample size because of the subjectivity involved in making the judgement of softness)……..

- Some sharing of the different types of enquiry (see Blog 1), and giving examples of each type, is a useful exercise at the start of Stages 5 and 6.

Then given a list of questions (chosen to illustrate the range of enquiries) learners can then be asked how they would go about finding the information needed to answer each one. This is again designed to provide learners with the knowledge needed to make decisions themselves. In this case the learners will develop the skills to decide on an appropriate methodology to answer their own questions. A really good open ended question will define the context of the enquiry, but won’t dictate the independent (‘the thing we change’) or dependent variable (‘the thing we measure’). Look at the following examples:

- “What affects the way sugar dissolves?” (an open question that sets the context of an enquiry but does not give away either variable)

- “What affects the time it takes sugar to dissolve?” (in this question the dependent variable – i.e. the time to dissolve – is given away before we start)

- “How does temperature affect the time it takes sugar to dissolve?” (in this closed question both the independent variable, i.e. temperature, and the dependent variable, i.e. the time to dissolve, are chosen by us, excluding the learners from making important decisions).

The last closed question may be appropriate if concentrating on other aspects of skill development, but skilful open ended questioning can always arrive at the same point and provide a more interesting start to your lesson.

REFLECTION SECTION

- Have you ever used ‘unfair testing’ to stimulate planning skills? If so, which investigations have you tried it in? Did the children enjoy the approach?

- Can you think of any investigations that are too difficult to resource or unsuitable for children to try themselves that could be used to teach planning skills using this strategy? Think about an example and how you would plan your lesson.

- If the Planning frame poster had been introduced in your school in Stage 2, when do you think the majority of learners would be ready to start using the A3 paper Planner independently?

- What questions would you include on a Help Sheet designed specifically for the next investigation your class will tackle?

- Which questions could you omit to simplify the Help Sheet above for the lower attaining learners in your class?

- Think of a ‘Which-type’ investigation that you could tackle with your class.

- As a means to differentiate this ‘Which-type’ investigation, consider which learners in your class would be best suited to trying the simplest of tests between two values of the categoric variable. How would the investigation differ for the higher attainers in your class?

- How to make this question more open ended: “How does the angle of the slope affect how far a toy car rolls?” Start with a question that just gives away the dependent variable, then a question that only sets the context of the investigation

- Think of a few examples of ‘Which – type’ investigations that could stimulate learner’s ideas by introducing the enquiry with the question, “Which ……… is best?”

- How do learners tackle planning a fair test in your class?

- What do they record?